|

Judah P. Benjamin

(1811-1884)

A worthy Namesake

Scholar - Statesman -

Queen's Counsel

From humble beginnings, Judah P.

Benjamin would become the first American Jew

to hold a number of significant public

positions, and would successfully carved\ out

three separate distinguished public

careers under the flags of three

different nations. His

intellect, affable personality, work

ethic, business acumen, and his oratory

and communication skills lead to his

meteoric rise and contributed greatly to

American history. Though ridiculed

by Northern anti-Semites, the South

welcomed Benjamin into her bosom,

allowing him to rise to heights no other

Jewish-American would rise to for

decades in America.

Early

Years:

Judah Philip Benjamin was born in

the British Virgin

Islands to Sephardic English immigrant

parents (Philip and Rebecca de Mendes

Benjamin) who were of Dutch and

Portuguese extraction. He was

brought to North Carolina at around age

two. At first the family lived in

Wilmington where Philip was in business

with uncle Jabob Levy. In 1817,

the Benjamins followed Mr. Levy up the

Cape Fear River to Fayetteville, NC.

There young Judah received his first

formal education at a private academy

run by Scottish Presbyterian minister

Colin McIver. In 1819, an economic

downturn left Mr. Levy broke and the

Benjamins relocated to Charleston, South

Carolina. Benjamin, a good

student, was admitted to a private

academy in Charleston run by Rufus Southworth,

financed by the Hebrew Orphan Society.

A

brilliant child, at age 14 he studied

law at Yale. But without completing his

studies he moved to New Orleans.

Making His

Mark:

In

New Orleans, Benjamin clerked for a

notary. This a position enabled

him to learn routine legal procedures

and read law in his spare time. He

also supplemented his income by teaching

English to French-speaking Creoles, an

activity that brought him into contact

with the wealthy St. Martin family.

He was admitted to the Bar in December

1832,

then

established his own practice of law.

On

February 12, 1833, at age 22, he married

16 year old Natalie St. Martin in a

Catholic Ceremony. At age 23

Judah wrote a reference book on law that

that became a standard text for lawyers

and judges in the State. As his

practice prospered, his new life of money

and fine things seemed to make his new

bride Natalie

only momentarily happy.

In

1840 Judah bought a plantation

near New Orleans called "Belle

Chase". He wanted the

most beautiful, extravagant,

house in all of Louisiana. He

plunged into the work of the

plantation. He wanted to show

the South that sugar cane could

be its future. Sugar

production was in its infancy in

Louisiana. Judah brought new

varieties of seeds from France

and new advanced growing

techniques. Planters came from

all over the state to dinner

parties with experts from all

over the country. Natalie was

miserable in his prosperous new paradise, but

they finally had a child after

ten years of marriage.

In 1844 Natalie took their child

and moved to Paris.

Benjamin then invited his

recently widowed sister, her

daughter, and his mother to live

with him. Judah did not

let Natalie’s departure, the

ensuing pain, and embarrassment,

deter him from carrying out the

plans he had for Belle Chasse.

He tore down the old house and

built a mansion surrounded by

double balconies supported by

twenty-eight square cypress

columns. It had twenty rooms

with 16 foot wide hallways,

crystal chandeliers, a marble

fireplace, a spiral mahogany

staircase and a veranda around

the entire house. Since Belle

Chase was not a plantation

handed down to him by an earlier

generation, he came to slave-owning later in life.

Judah purchased 140 slaves.

Judah took care to have a

plantation noted for its

humaneness and sought to be

known across Louisiana as a

gentleman that treated his

slaves well. |

|

In 1852,

the flooding Mississippi reached the

very steps of Belle Chase. The crop of

sugar was destroyed and Judah did not

have the time to supervise its

replanting. He decided to sell Belle

Chase for a sum large enough for him to

retire the debt, buy a fine house in

Washington, and move his family to the

elegant home. His years as a planter

were ended.

Public

Life:

Louisiana Legislature

- Benjamin was elected to the

Louisiana legislature in 1842.

1st

Jewish American in the U.S. Senate -

In 1852, he was elected to the U.S.

Senate from Louisiana. This would

make the Honorable Judah P. Benjamin of

Louisiana the first acknowledged Jew

elected to the US Senate (1852).

Florida’s first Senator, David (Levy)

Yulee (elected in 1842, claimed he was

not Jewish at all, but descended from a

Moroccan prince. Thus because Benjamin

acknowledged his Judaism, it can be said

he took his seat in the halls of history

as the first acknowledged Jew in

America’s most influential legislative

institution.)

U.S.

Supreme Court Nomination- Senator

Benjamin was so eloquent and so well

thought of by two Presidents that

he was offered nomination to the U.S.

Supreme Court

(Millard Filmore - 1852 and Franklin

Pierce - 1854). Benjamin

declined on as he could not serve and

maintain his law practice.

Had he accepted, he would have been the

first Jewish American appointed to the

U.S. Supreme Court. Consequently,

62 years later the first would become

Louis Brandeis

in 1916,nominated by

President Woodrow

Wilson.

Famous New Year's Eve

Speech on Senate Floor - Often

regarded as his "farewell speech" to the

Senate,

historians consider Benjamin’s farewell

address to the U.S. Senate on New Year’s

Eve, 1860, one of the great speeches in

American history. The Senate gallery was

packed to hear the most eloquent voice

of the south. It was a moment both of

tragedy and triumph as he pleaded with

his colleagues against the war of

brothers to come:

“And now Senators…indulge in no vain

delusion that duty or conscience,

interest or honor, imposes upon you the

necessity of invading our States or

shedding the blood of our people. You

have not possible justification for it.”

Varina Davis, soon to become the

Confederate First Lady, wrote that

“his voice rose over the vast audience

distinct and clear…he held his audience

spellbound for over an hour and so still

were they that a whisper could be

heard…”

“[Benjamin continued] What may be the

fate of this horrible contest, no man

can tell…but this much, I will say: the

fortunes of war may be adverse to our

arms, you may desolate into our peaceful

land, and with torch and fire you may

set our cities in flame…you may, under

the protection of your advancing armies,

give shelter to the furious fanatics who

desire, and profess to desire, nothing

more than to add all the horrors of a

servile insurrection to the calamities

of civil war…but you can never subjugate

us, you never can convert the free sons

of the soil into vassals, paying tribute

to your power; and you never, never can

degrade them to the level of an inferior

and servile race. Never! Never!”

There was an immediate rush of reaction

to the speech from the Southern

contingent and tumultuous applause from

the galleries. Mrs. Davis reported

that

“many ladies were in tears. The Vice

President tried in vain to prevent the

applause but could not control the

multitude who were wild with enthusiasm.

There were even grudging compliments

from the Northern press and a quote from

a London correspondent that “it was

better than our Benjamin [Disraeli]

could have done.”

The enthusiasm in the South was matched

by the venom with tones of anti-Semitism

in the North. The Boston

Transcript of January 5, 1861, published

an editorial under the heading “The

Children of Israel” in which it attacked

the support Benjamin and other Southern

Jews gave to secession as indicative of

the disloyalty of all American Jews.

Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts,

who would be elected Vice President of

the United States in 1872, condemned

Benjamin because

“his bearing, his tone of voice, his

words, all gave evidence…that his heart

was in this foul and wicked plot to

dismember the Union, to overthrow the

government of his adopted country which

gives equality of rights even to that

race that stoned prophets and crucified

the Redeemer of the world.”

Confederate

Cabinet

- Louisiana would secede from the Union

in February 1861, and accordingly,

Benjamin did resign from the U.S.

Senate.

President Jefferson Davis appointed

Benjamin as his Attorney General on

February 21, 1861. The President chose

him because, in Davis's own words,

he "had a very high reputation as a

lawyer, and my acquaintance with him in

the Senate had impressed me with the

lucidity of his intellect, his

systematic habits, and capacity for

labor." Benjamin plunged into the

cabinet policy debates on all aspects of

the Confederacy and developed a

reputation as one who loved details,

complexity, and problem solving.

He would become known as the "Brains of

the Confederacy".

Confederate President Davis' appointment

would catapult Benjamin to the lofty

status of becoming the 1st

Jewish American cabinet member.

(Not until 1906, would a USA President

make a similar appointment - Oscar Straus was

appointed Sec. of Commerce and Labor by

President Taft).

Later, Benjamin was appointed Secretary of

War. He didn’t have a military

background, but in this role, he was the

mouthpiece for Jefferson Davis, himself,

deflecting criticism that could have

been leveled on Davis, his affable style

able to "smooth over" feathers Davis

ruffled. In her autobiography,

Jefferson Davis’s wife, Varina, informs

us that Benjamin spent twelve hours each

day at her husband’s side, tirelessly

shaping every important Confederate

strategy and tactic. Yet, Benjamin never

spoke publicly or wrote about his role

and burned his personal papers before

his death. He acted as an intermediary

and mouthpiece, but always following

Davis’ orders. His last post was as

Secretary of State, and it was under him

that the Seal of the Confederacy was

commissioned, as a way to gain prestige

in England. He worked to enlist aid

from England and France, in diplomatic

recognition of the Confederate State of

America.

Escape from Capture - Fearing

capture and imprisonment (President

Davis and Vice President Stephens were

both captured and imprisoned), with a

immense $40,000.00 (a half million in

today's dollars) bounty imposed by the

U.S. Government, Benjamin embarked on a

harrowing escape. He had planned

for the eventuality, and developed a

disguise - a Frenchman seeking

land on which to settle. He was

able to speak broken English like a

Frenchman, and he wore a disguise of a

hat, goggles, cloak, and full beard,

which he had recently grown. What

is sometimes also cited is the fact that

he had a Colonel H. J. Levy with him as

a traveling companion through Georgia.

It is also alleged that before he left

Richmond he had a Confederate passport

made which stated he was a Frenchman

traveling through the South. Most

sources also note that he used an alias

as part of his Frenchman ruse, either

M.M. Bonfals, Monsieur Bonfals, or just

Bonfals. If he really did use this

alias, it shows that the fleeing

Benjamin, who lived most of his adult

life in New Orleans, Louisiana, still

had a sense of humor. Bonfals is

French/Cajun for "good disguise".

Hillsborough County, Florida men are

credited with aiding his escape: Capt.

McKay and Major John T. Lesley, of the

Florida Cow Cavalry, who whisked him to

Gamble Mansion, where he stayed a few

nights before sailing from Sarasota Bay

to the West Indies, evading Union men

who would get rich if they were able to

capture and turn in Sec. Benjamin.

Traveling in an open yawl, surviving

both storm and fire at sea and with

stops in Bimini, Nassau, and Havana,

Cuba, Benjamin finally arrived in

Southampton, England on August 30, 1865

Practice in England:

. Claiming British citizenship by birth

he set about starting over in London at

age 54. Though he had money to pay for

his passage he earned income writing

newspaper and magazine articles.

He started over as an ordinary law

student and but his ability was quickly

recognized and in 1866 he was called to

the Bar. He rapidly made a success of

his practice as a barrister, so much so

that, when an 1868 general amnesty made

it possible for him to return to America

openly, he had no desire to leave

England.

He wrote a text commonly called

"Benjamin on Sales" (1868) that is still

a classic in the field of British

transactional law, and is studied today.

Taking Silk (becoming Queen's Counsel)

in 1872 in Lancashire County, he became

the first Jew, and man not born in

England, to be so honored. As Benjamin's

legal stature and wealth increased

judgeships were offered and declined as

he knew he would never be able to afford

the 'promotion'.

He

became so successful that by 1877, he

would accept no case for a fee of less

than 300 guineas ($1,500). In 1879 a New

York Times correspondent estimated his

income to be $150,000 (over $3 million

in today's dollars).

Final

Years:

In

preparation for his retirement Judah

built a large mansion in Paris, France.

The mansion was completed in 1880.

Natalie moved back in with him. But a

severe heart attack brought on by

diabetes on Christmas, 1882 forced his

retirement. Benjamin died on May 6,

1884, in Paris, at age 73, at his

mansion. Varina Davis wrote, “ Thus

passed from earth one of the greatest

minds of this century.” Natalie had him

buried in a crypt marked only for the

families of St. Martin and Bousignac.

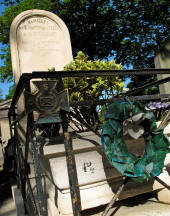

In 1938, the Paris Chapter of the United

Daughters of the Confederacy, added this

inscription to his grave:

|

|

|

Judah Philip Benjamin

Born St. Thomas West Indies,

August 6, 1811

Died in Paris May 6, 1884

United States Senator from

Louisiana

Attorney General, Secretary

of War and Secretary of

State of the Confederate

States of America

Queen’s Counsel, London |

Because

of its significance in his escape,

Manatee County’s (Florida) Gamble

Mansion was preserved by the Judah P.

Benjamin Chapter of the United Daughters

of the Confederacy and is now known as

the Judah P. Benjamin Confederate

Memorial at Gamble Plantation Historic

State Park.

Today both

the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the

United Daughters of the Confederacy

bestow awards. The UDC's award is

bestowed to any individual for

outstanding achievement not necessarily

related to the Confederacy in the fields

of civic/community service,

conservation, education, the

environment, humanitarian efforts, and

patriotic service.

The SCV's award is an internal award for

the Camp over 50 members maintaining the

best scrapbook of its activities over

the past year. |